The Dissemination of the Term Vibe Coding

Andrej Karpathy, a Slovak-Canadian computer scientist with a distinguished background in Artificial Intelligence (AI), notably as the former director of AI at Tesla and a co-founder of OpenAI, first coined the term "vibe coding" in February 2025. His extensive experience in deep learning and computer vision, including his role as the primary instructor for Stanford's first deep learning course, CS 231n, positions him as a respected voice in the AI community.

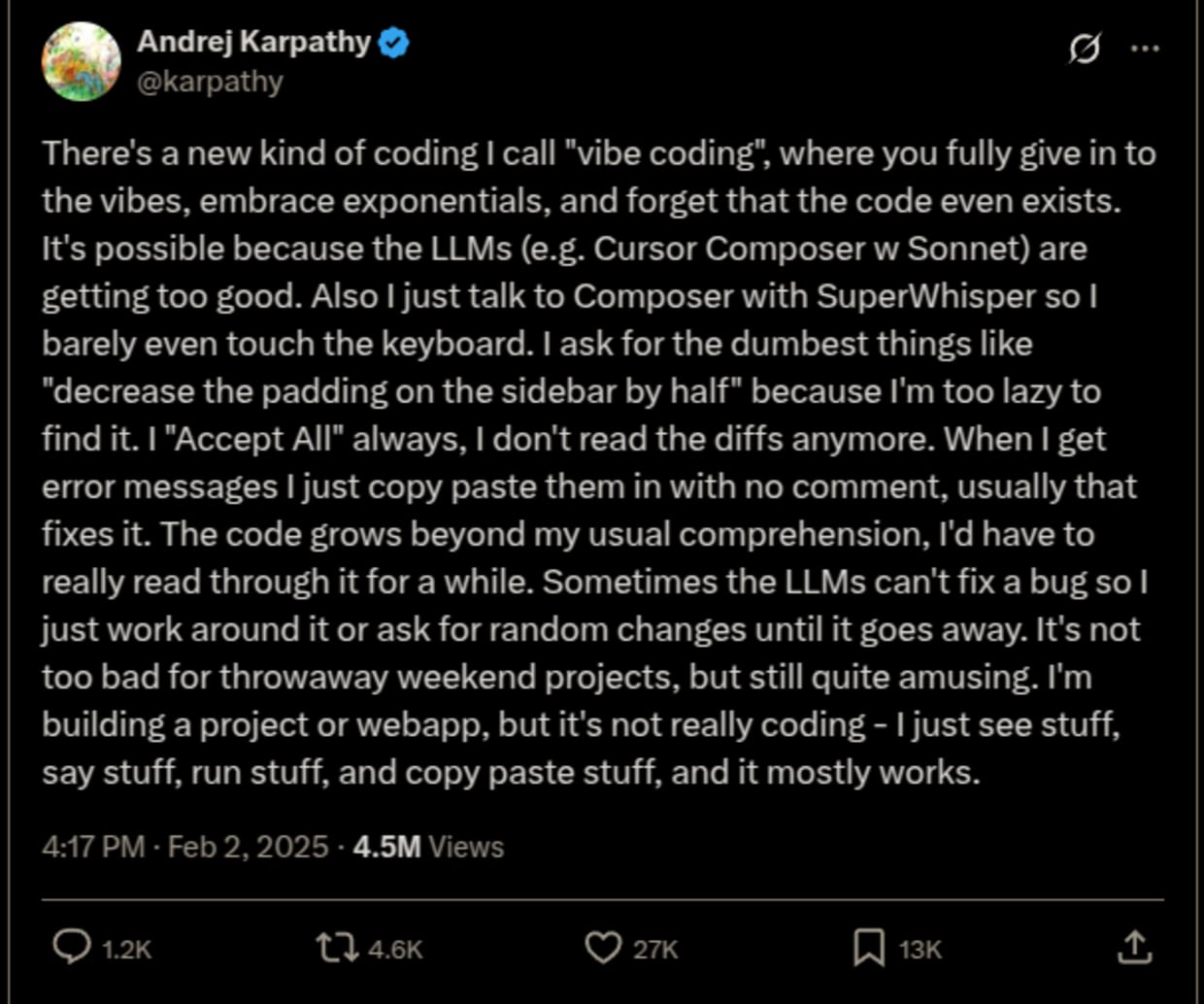

On February 2nd, 2025, Karpathy posted on X/Twitter describing a new approach he called "vibe coding," where developers "fully give in to the vibes, embrace exponentials, and forget that the code even exists." This wasn't just another hot take from a tech leader; it was a crystallization of something many developers were already experiencing but hadn't named yet.

Karpathy explained his workflow: using voice commands through SuperWhisper to minimize keyboard interaction, making simple requests like UI adjustments, routinely accepting all suggested changes without scrutinizing the differences, and, when encountering errors, simply copying and pasting them back to the AI. He acknowledged that this approach led to code growing "beyond [his] usual comprehension" and that bug fixing sometimes meant "working around issues or making seemingly random changes until problems disappear."

What is vibe coding?

Vibe coding is a deliberately casual approach to software development where developers (including those without formal background, education, or experience) use AI assistants to write code with minimal oversight or understanding of what's being generated. Rather than carefully reviewing every change, vibe coders trust the AI's output, accept suggested modifications wholesale, and treat error messages as input to feed back to the AI rather than problems to personally debug. This is not an inherently bad thing. It is great to see more code being written and the process becoming more accessible to less technical users.

The code itself becomes almost secondary; what matters is whether the application feels like it's working. It's programming by “vibes” rather than by comprehension, prioritizing speed and iteration over traditional software engineering practices, such as code review, testing, and maintaining a mental model of your codebase. At its extreme, vibe coding means building applications where you couldn't explain how most of the code works, because you didn't write it and didn't really read it either.

It's everywhere

The viral spread of "vibe coding" happened at internet speed. Within hours, Amjad Masad, CEO of Replit, responded, noting that approximately 75% of Replit's user base already engaged in coding without writing code themselves, suggesting that Karpathy hadn't invented a new practice so much as named one that was already widespread.

By February 12, an X thread by @rileybrown_ai, sharing "15 rules of vibe coding," received over 10,000 likes. The tech community was off to the races, creating memes, think pieces, and hot takes at breakneck speed. An X user @IterIntellectus created a Rick Rubin headphones meme for vibe coding that received 3,000+ likes, making Rick Rubin the unofficial "face" of vibe coding—a fitting choice given Rubin's legendary intuitive, vibe-based approach to music production.

By February 13, Business Insider published "Silicon Valley's next act: bringing 'vibe coding' to the world," marking the first major tech media coverage of the concept. The New York Times followed on February 27 with Kevin Roose's piece "Not a Coder? With A.I., Just Having an Idea Can Be Enough."

On February 24, Gitpod published "'Vibe coding' is a revolution for optimistic creatives," calling vibe coding "a symbol of optimism and a coming wave" and reporting that they created physical "vibe coding" stickers for the AI Engineering Summit.

Perhaps the most telling indicator of mainstream acceptance: by March 1, Merriam-Webster had added "vibe coding" as a slang term, defining it as "writing computer code in a somewhat careless fashion, with AI assistance." From tweet to dictionary in less than a month. That's not just viral; that's a cultural moment.

Y Combinator's CEO Garry Tan reported that 25% of their Winter 2025 batch startups had codebases that were 95%+ AI-generated, suggesting this wasn't just people playing around—entire companies were being built this way.

But as the enthusiasm grew, so did the cautionary tales. By mid-February, X user @Brycicle77 resurfaced a Reddit post showing a user lamenting their "project entirely built with Cursor and Claude" that had become unmanageable: "30+ Python files, disorganized code, duplicate loops... Claude keeps forgetting imports." The caption wryly noted: "Vibe coding and its consequences."

Do the vibes really be coding though?

Not securely.

This is where the vibe hits a wall. While developers were enthusiastically accepting all changes and copy-pasting error messages, serious security vulnerabilities were piling up in production codebases.

In one notorious case documented by security researchers, a developer used AI to scaffold a SaaS app but unknowingly exposed their OpenAI API key in client-side code. Attackers discovered the leaked key within minutes, and the developer "had to negotiate with OpenAI to forgive his bill." The vibes were expensive.

Several vibe-coded projects suffered from broken authentication flows, with one review finding that AI-generated authentication code sent OpenAI API keys over the network in plaintext, visible to any user via developer tools.

A particularly troubling incident involved an AI-generated web game that went viral, along with a serious Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) vulnerability that put thousands of users at risk. The developer had "vibe-coded" the app using ChatGPT, trusting its output. Security researchers warn that AI copilots can introduce SQL injection flaws, XSS vulnerabilities, and data leaks if code is blindly accepted.

One vibe coder accepted AI-recommended code for a community plugin which harbored an input sanitization flaw that later allowed a stored XSS on their site, mirroring the pattern of "vulnerabilities found in poorly maintained WordPress plugins."

And it wasn't just individual projects. On March 18, 2025, a "Rules File Backdoor" vulnerability was discovered affecting GitHub Copilot and Cursor—two of the most popular tools for vibe coding. This was a systemic vulnerability in the infrastructure that enabled the practice itself.

The pattern became clear: vibe coding dramatically accelerates development, but it also dramatically accelerates the introduction of security vulnerabilities. Research from Wiz found that one in five organizations building on vibe-coding platforms inadvertently expose themselves to risk through common misconfigurations.

As one security analyst put it: "The AI missed critical authorization checks that a human would have caught," referring to an authentication system that worked in testing but lacked critical role verification, leading to an exploitable admin privileges bug.

The fundamental issue? When you don't understand the code you're deploying, you can't assess its security implications. The vibes might be immaculate, but the threat model is nonexistent.

Making vibe coding accessible

Despite the security concerns, there's something genuinely revolutionary happening here: programming is becoming accessible to people who were previously locked out.

For years, we've talked about "low-code" and "no-code" platforms as the great democratizers of software development. But they often came with limitations—rigid templates, constrained functionality, and a ceiling on what you could build. Vibe coding, by contrast, offers something closer to the full power of programming through natural language.

Voice coding—using speech instead of a keyboard—has gained significant traction alongside vibe coding, spurred by advances in speech recognition technology, such as OpenAI's Whisper. This convergence is particularly powerful for accessibility.

The timeline of voice coding tools shows steady progress throughout 2024. By March 2024, Aqua Voice (a Y Combinator startup) demonstrated the growing interest in voice coding by launching a voice-driven text editor claiming "7× fewer errors than macOS dictation." Tools like Serenade, an open source speech-to-code engine that allows users to write code using natural speech and integrates with editors like VS Code, matured significantly.

At the CSUN Assistive Technology Conference 2025, a session on AI for coding showcased how voice coding tools empower programmers with motor disabilities to participate more fully in software development. One speaker demonstrated using Serenade with GPT-4 to build a web app purely by voice.

This matters enormously. Programming has long been an incredibly physical activity—hours of typing, precise motor control, navigating complex keyboard shortcuts. Voice interfaces combined with AI assistance open the door for people with RSI, motor disabilities, or other conditions that make traditional coding challenging or impossible.

But accessibility goes beyond physical ability. It's also about cognitive accessibility—the ability to express what you want without needing to know the syntax, the libraries, the patterns. For someone who understands their problem domain deeply but lacks programming knowledge, vibe coding offers a bridge.

The challenge for product designers and UX researchers is figuring out how to make these interfaces safe and effective for non-technical users. Microsoft's Power Platform Copilot enables users to create apps through natural language, with administrators able to define what Copilot is allowed to do, ensuring citizen developers don't unknowingly expose sensitive data.

Salesforce introduced an AI Copilot that helps administrators build automation flows with text-based instructions. For example, a Salesforce admin can type "When a high-value lead is created, assign it to a senior sales rep and send an email alert," and the AI will produce a Flow that implements this functionality.

These platforms are wrestling with a fundamental question. How do you give non-technical users the power to create software while protecting them from the hazards they don't know exist?

And this time, it's personal

There's another dimension to vibe coding that deserves attention: personalization.

Traditional software development has been oriented toward building applications for others—whether that's enterprise software, consumer apps, or open source tools. But what if the fastest path to a personalized experience is building it yourself, in the moment, through conversation?

Karpathy reported building a "Battleship" game and an "LLM text reader" app in approximately one hour each, issuing all instructions by voice. These weren't products meant for distribution; they were personal tools, built for his own use, optimized for his own preferences.

This points toward a future where software becomes more like cooking than buying prepared meals. Instead of choosing from a menu of existing apps and trying to bend them to your needs through settings and customization options, you might simply describe what you want and have it built for you.

We're seeing hints of this with the latest generation of AI models. Google's Gemini has been experimenting with using your search history to personalize responses. The models are getting better at understanding context, at remembering what you care about, at adapting to your specific needs.

But here's where things get interesting and a bit fraught: LLMs sometimes produce incorrect or outdated code for using the APIs associated with those models. This isn't about the models knowing their own weights or architecture—that would be a different kind of problem. It's simpler and more frustrating: models like ChatGPT are trained on vast datasets that include documentation up to a certain cutoff date. If their API or SDK changes after that date, the model won't know about it unless explicitly fine-tuned later.

I've experienced this personally. When trying to use ChatGPT to write code for OpenAI's own API, I've often received outdated syntax or deprecated methods. On OpenAI's developer forum in November 2024, one user complained: "GPT-4 consistently produces outdated code for its own API in Node.js. Even when I give it a link to the latest docs, it ignores it and returns the same old code."

The irony is rich: AI companies are racing to make coding accessible through conversational interfaces, but their own models struggle to stay current with their own rapidly evolving APIs. One user noted that ChatGPT was still showing examples using an older version of the openai Node library with callbacks or older parameter names, or using deprecated endpoints like Completions.create instead of the newer ChatCompletion.create.

Interestingly, Claude (made by Anthropic) often does better at generating code for OpenAI's API than ChatGPT itself. Perhaps because Claude's training included more diverse sources and wasn't as heavily weighted toward older OpenAI documentation.

This highlights a fundamental challenge as models try to personalize and adapt: they're always working from slightly outdated information. While knowledge cutoffs have improved substantially (from 18+ months to around six to eight months), this lag still creates significant blind spots when generating code for rapidly evolving frameworks and APIs.

In the end, all we have is each other

Let's zoom out for a moment.

When ChatGPT first emerged in late 2022, people were in disbelief that AI could code at all. The idea that you could describe a program in English and get working code seemed like science fiction. Now, less than three years later, we're debating the wisdom of "vibing" entire applications into existence while barely reading the code.

The speed of this transformation is genuinely disorienting. And it's easy to focus on the risks—the security vulnerabilities, the technical debt, the maintainability nightmares. These concerns are real and serious.

But there's something else happening here that's worth celebrating: more people are building things.

Y Combinator CEO Garry Tan praised vibe coding for letting small teams achieve more, saying AI coding tools allow "10 engineers do the work of 100." Artists, designers, domain experts who never would have learned traditional programming are now creating functional software. People with disabilities who were excluded from coding are finding new pathways in.

Yes, some of these projects will have bugs. Yes, some will have security issues. Yes, the code will sometimes be a mess. But you know what? That was also true of the early web, of mobile apps, of every new wave of software development. We learned. We developed better practices. We built better tools.

The consensus emerging was that vibe coding "feels like a cheat code... but once you step beyond toy projects, reality checks in hard." That's probably healthy. Vibe coding has found its niche: rapid prototyping, personal tools, weekend projects, and exploration. For production systems handling sensitive data or critical functions, we need more rigor.

Developers and security experts are establishing best practices for AI-generated code, such as treating AI like a junior developer whose code must be reviewed, running static analysis and linters, using tools like Snyk's DCAIF to automatically patch vulnerabilities, and explicitly prompting the AI about security requirements before coding.

Namanyay Goel published "Karpathy's 'Vibe Coding' Movement Considered Harmful" on March 27, calling blind trust in code generation a "fundamental breakdown in engineering responsibility." He's right. But he also acknowledged that AI copilots are powerful tools when used responsibly.

The future of software development will likely involve a collaborative partnership between human developers and AI tools. Vibe coding represents an early, somewhat chaotic stage of this collaboration. It's messy. It's exciting. It's occasionally reckless. It's enabling people to create things they couldn't have created before.

Simon Willison helpfully clarified that "not all AI-assisted programming is vibe coding," distinguishing routine use of tools like Copilot from Karpathy's extreme "trust the AI" approach. There's a spectrum here, and most of us will probably land somewhere in the middle, using AI to accelerate our work while maintaining understanding and oversight.

Maybe the real lesson of vibe coding isn't about the code at all. It's about experimentation, about lowering barriers, about giving people permission to try things even if they don't fully understand them. That's always been how people learn to code—by copying examples, by trial and error, by breaking things and fixing them.

The AI just makes the cycle faster.

So vibe away, but maybe keep one eye open. Read at least some of the diffs. Run those security scanners. Ask questions. Learn. And when your vibe-coded project inevitably has issues, remember: debugging is where the real learning happens anyway.

In the end, all we have is each other. Humans and AI that is by and for humans, figuring this out together.

ON-DEMAND WORKSHOP

Securing Vibe Coding: Addressing the Security Challenges of AI-Generated Code

Snyk Staff Developer Advocate Sonya Moisset breaks down the security implications of Vibe Coding and shares actionable strategies to secure AI-generated code at scale.